Designing Our Way Out of Loneliness

How spatial design can tackle one of society’s biggest mental health problems

How spatial design can tackle one of society’s biggest mental health problems

Loneliness is a killer. Its impact on our health has been likened to that of smoking 15 cigarettes a day, knocking an estimated eight years off the average life span. It is set to outstrip obesity as one of the biggest health issues of our era. And nowhere is it more prevalent than in our urban environments. Cohousing could be a way to face this challenge.

The rise of an urban lifestyle

The foundations for today’s loneliness epidemic were laid in the 19th century with the advent of mass urban immigration thanks to industrialization. Thousands of people left their families and friends, relocating to places filled with other individuals instead of collective, social units. As cities evolved into major economic hubs, this trend accelerated over time, and the rise of loneliness has been aided by poor urban planning and an ideological shift towards individualism.

“The way we design our cities has a direct impact on the way we feel, move and behave,” explains Paty Rios, an architect, urban planner and head of research projects at the Happy City consultancy in Vancouver, Canada. “The problem is that we have been designing with disregard of this effect and decisions that were taken a hundred years ago are still impacting in a negative way. Modern urbanism took a toll on the way people relate in a daily basis. Separating work, residence, industry and recreation caused major issues. People no longer moved in an organic way.”

“We have moved away from community and multigenerational living towards independence and autonomy,” adds architect Grace Kim, cofounder of Schemata Workshop in Seattle. “We have created a self-sufficiency that is isolating.”

Image of the rooftop farm at Schemata Workshop’s Capitol Hill Cohousing development. Photo © Danny Ngan

Skewed land values and piecemeal development still often result in the loss of shared spaces and pre-existing communities, while recent attempts to respond to the demand for more homes have seen a boom in housing estates with poor transport links and few communal spaces or shops where people might meet naturally.

Now, a growing number of architects and urban planners are turning their attention to loneliness as a design issue, partly in response to finger-pointing from politicians and pundits who use architecture as a scapegoat.

“If you go to the Far East, they are still building apartments and flats that are shoeboxes with relentless corridors, but they still have community. People are just used to living closer. So I don’t think architecture is the driver,” says Je Ahn, a founder of London-based architecture firm Studio Weave. “Architecture is a symptom – it is part of the way society has moulded us against reaching each other.”

Restoring a sense of community through architecture

Can architecture offer a realistic solution? Cohousing seems to offer one relatively easy way forward. There are various models of cohousing, but essentially it combines private space—from a bedroom to an entire house—with shared spaces like communal kitchens, laundry rooms and leisure spaces. When successful, the cohousing approach can foster connections between residents.

Schemata Workshop played a lead role in the development of the Capitol Hill Cohousing development in Seattle. The architecture firm occupies the building’s ground floor, while nine private apartments are arranged around a communal courtyard. Residents share The Common House, described as a “community room”, which is designed specifically for communal dining.

The Capitol Hill Cohousing complex by Schemata Workshop. Photo © Danny Ngan

“My observation has been that as the number of meals shared together weekly increases, the sense of community also seems to increase, so having The Common House to support the dining function is key to building community,” says Kim, who now runs workshops for architects to help them become cohousing specialists.

Last year, Studio Weave teamed up with the Royal Institute of British Architects to publish Living Closer, which examined various different types of cohousing in light of its growing popularity. Instead of finding favour with a particular model, the report encouraged diverse approaches.

But, Ahn warns, the current cohousing trend is not just about fostering better emotional lives for residents but also bottom lines for developers. “At the moment, it seems to be all about mechanics, financial instruments and spatial standards. A lot of this arises from the pressure to develop leaner, smaller, tighter projects and I think that’s just been clumped together with the more emotional side of things”, he says. “There is a big difference between physically living closer and emotionally and mentally living closer.”

Designer Edwin Van Cappelbeen has proposed a different approach that could be used to adapt existing buildings. As a student at Design Academy Eindhoven in The Netherlands, he lived in a building with 700 studio apartments. “Many tenants, including myself, didn’t know anyone that lived directly around them – not even their direct neighbours – because they felt that talking to people in the hallways was difficult”, he says.

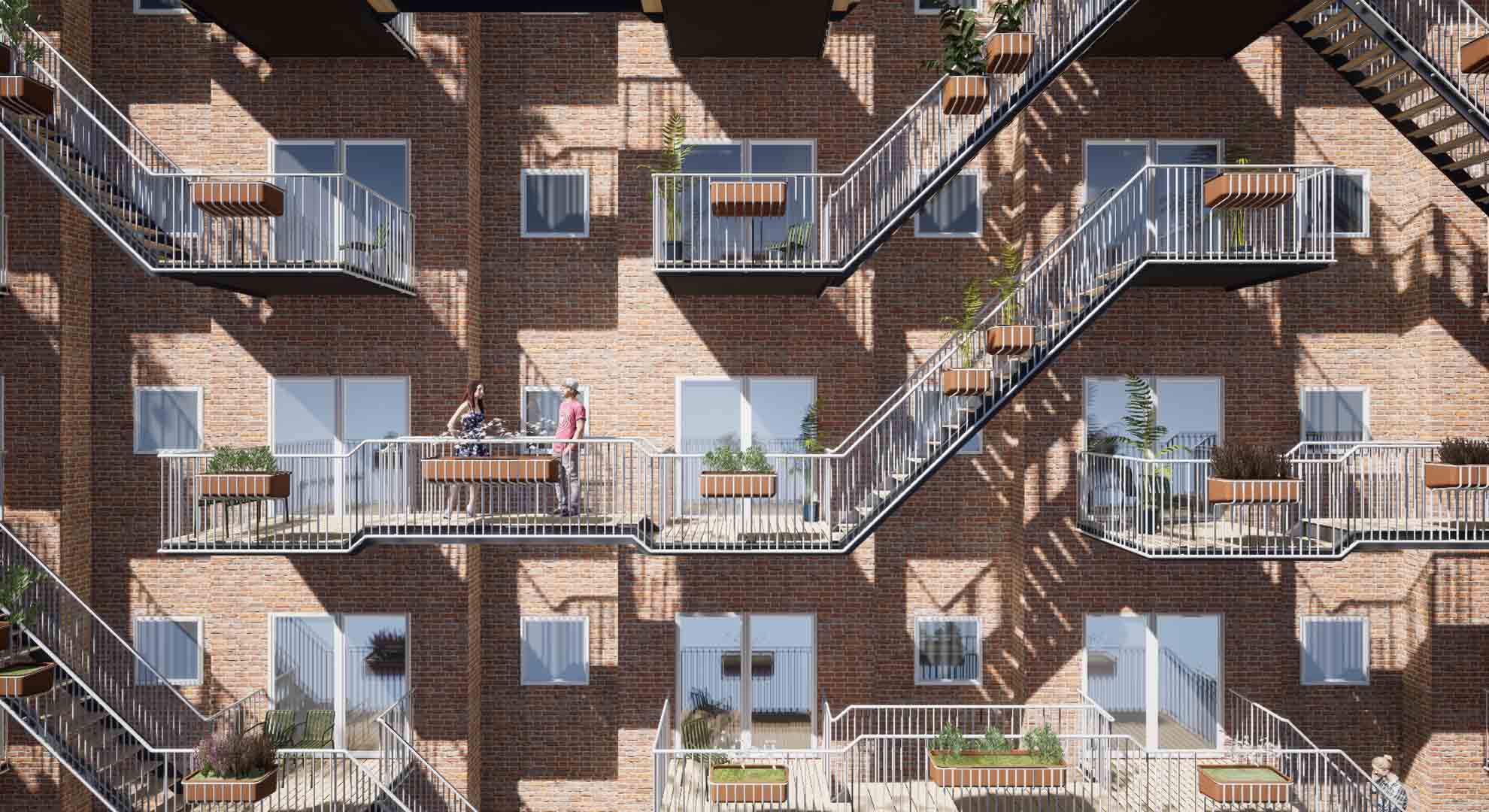

Social Balconies by Edwin Van Cappelbeen. Image courtesy of the designer.

Although some of the apartments had balconies, they were used mainly for airing laundry or ad hoc storage. This sparked the idea for Social Balconies, a proposal for modules that could be attached either to existing balconies or to reinforced steel beams to create a shared social space on a building’s facade, with planters to turn the new network into a kind of shared garden. “It engages neighbours into caring for plants collaboratively, which is an easy segue to small talk and shared activities,” he explains. With interest from investors and the city council, Van Cappelbeen is now working to create a functional prototype of his design.

Design is only part of the solution

Urban loneliness has pervaded in spite of our attempts at reinventing the way we live. Despite the best efforts of architects, planners and even idealistic development groups, many of today’s projects could be anecdotal unless there is a shift in government policy to support conversations and solutions that address the root causes of loneliness.

It is clear that architecture can only be part of the solution. Happy City’s team of urbanists, architects, policy specialists and strategists are among those who are aiming to effect change above the level of individual projects – they have been targeting governments and developers with their Happy Homes toolkit and are now tackling housing policy.

“Every faction of society needs to move together,” says Ahn. “Everyone should be in the conversation about how we want to live in this society and what it actually means… I would love a Prime Minister to actually talk about relationships between people, rather than the economy all the time. We need to talk about it more.”

Main image: The communal courtyard at Capitol Hill Cohousing development. Photo courtesy of Schemata Workshop